I’m pleased to say another poem from British Standards, a ‘transposition’ of the poems of John Clare, the first of that set to appear, as text, I think, is published in Beir Bua.

here: I love to see the old heath’s withered brake by Robert Sheppard – Beir Bua Press

Thanks to the noble editors involved. And you can check out the rest of the contents: journal – Beir Bua Press

Unthreading John Clare’s poems once or twice turned me into a bona fide animal poet (as the lockdown turned me, and everyone, into a bird watcher (and listener: the (possible) song thrush that appeared at 4.00 each afternoon finds his or her way into another Clare transposition, as do more common blackbirds, into another, with their ‘chup-chup’!)).

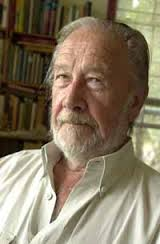

Here I am with a ‘flash of yellow-green’ in my borrowed hat reading the poem I love to see the old heath’s withered brake (or its draft) on the day I wrote it, 16th December 2020, looking daft for my draft, as it were:

On the fallen ash stump, a

robin

poses, without sharp

trill, all

life in its eye –

out of the

generation that

love-struck

Audubon

sketched

here, snatched

in a line’s

quick fling.

Here’s a different robin (I think, though it could be the one he sketched at Greenbank) painted by Audubon:

Although the Victoria Gallery was closed to the public when I wrote the poem, I remembered seeing in an exhibition there that Audubon had stayed in Greenbank House, which is just a few minutes’ walk from where we live, with the Rathbone family, and that he was love sick while there, AND that he had drawn a robin. I couldn’t re-visit the gallery, but I could have found it all online here (but used my memory of earlier visits instead):

Audubon Gallery - Victoria Gallery & Museum - University of Liverpool

The story of Audubon in Liverpool is told here:

John James Audubon - Victoria Gallery & Museum - University of Liverpool

(He’d also turned up in my reading of Denise Gigante’s The Keats Brothers. Cambridge, London: Harvard University Press, 2011, where he diddles George Keats out of all the money he and brother John had tried to extract from their ‘benefactor’. So he fluttered across two of my poets in British Standards).

The dedication to Christopher Middleton benefits from explanation. Often thought of as one of our great experimentalists (correctly!) he was also a great writer of animal poems, and I was thinking of his poem ‘How to Listen to Birds’, with its terrific, and suggestive, ending:It

modifies the whole

Machine

of being: this

Is

not unpolitical.

(Neither is my poem, I'd like to hint.) I have written about Middleton a number of times on this blog, and off it too, and this link will take you to one of those with spiders’ web links to other posts: Pages: Christopher Middleton (1926-2015) i.m. (robertsheppard.blogspot.com). Here’s my take on his poetics, on ‘measuring experience’: Pages: Robert Sheppard: Inaugural Lecture PART 2: Measuring Experience (on Christopher Middleton).

‘British Standards’ is also Book Three of a longer project of refunctioning traditional English sonnets, called ‘The English Strain’.

Book One of ‘The English Strain’, and Book Two, Bad Idea, are reviewed here: Review - "The English Strain" and "Bad Idea" by Robert Sheppard | Litter (littermagazine.com)