I explained here my task in editing Mary Robinson’s Selected Poems: See the hub-post here: Pages: Selecting for a Selected: The Poems of Mary Robinson 1 (robertsheppard.blogspot.com) .

It's now (June 2024) out: The Selected Poems of Mary Robinson is now out from Shearsman – edited by me!

Publisher’s details HERE: Mary Robinson - Selected Poems (shearsman.com)

The publisher's sample of the book may be read here: mary-robinson-selected-poems-sampler.pdf (cdn-website.com)

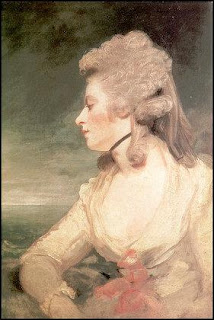

This project came out of my own use of Robinson’s sonnets for my ‘English Strain’ project, which I talk about here: Pages: My 'Tabitha and Thunderer' is published in Blackbox Manifold (robertsheppard.blogspot.com), and here, you'll also find lots of images relating to her: Pages: My Transpositions of Mary Robinson's sonnets 'Tabitha and Thunderer' are now complete (hub post) (robertsheppard.blogspot.com). I provided a brief life for my versions, ‘Tabitha and Thunderer’, but here I offer a (still brief, but I hope full and accurate) life of my subject for use in the Selected. It’s still not quite finished, because I need to read the third biography of her, to triangulate my information, as it were. THREE biogs came along at once, like buses, during 2004-5. And here I am, looking back at her life, having used it for my own poems. Her life is remarkable, and I recommend the biographies (either of the two I’ve listed below, and I’ve no reason to believe the third inferior). In many ways, you couldn’t make it up, as they say. By which people mean: if you had made it up, no one would believe you, a life that weaves Garrick, Sheridan, the Prince Regent, Marie Antoinette, a war hero, William Godwin and Coleridge together in one fabric. In many ways it is like the life of Mina Loy in the Twentieth Century. (Both had to deal with the advantages and disadvantages of great beauty, of course.) Why there are no bio pics of either is a surprise (though there are novels with Mary Robinson in, a Jean Plaidy at least from the 1960s). Below I give you the bare bones.

Mary Robinson was born Mary

Darby in Bristol in 1758. Her father was a commercial explorer operating in

Canada, away from home during most of Mary’s childhood, and living with a mistress.

(Later he would become a distinguished naval officer, partly in the British,

but notably in the Russian, navy). In Bristol, Mary received a progressive

education for a girl, at one of the schools run by poet Hannah More (or her

sisters), and later, in London, where the family moved to be closer to Darby on

his infrequent returns to Britain. Although the stage was regarded as an

inappropriate profession for a woman, theatre (and writing) had been part of

Mary’s education, and her acting skill was taken up by the leading dramaturge

of the era, David Garrick.

At 15½ she was married to Tom Robinson, who claimed to be

a rich heir, but was, in fact, the illegitimate child of a well-off Welsh

landowner, who had no intention of lending or bequeathing money. The couple,

installed in extensive premises, with all the trappings of extravagance, such

as a phaeton, lived well beyond their means, entertaining, and being

entertained by, the fashionable ton. In 1774 their daughter, Maria

Elizabeth, was born. Although Mary had renounced the stage on marriage, her

husband’s financial irregularities, which led to the couple being imprisoned

briefly as debtors, forced Mary to become a professional actor, this time

chiefly under the tutelage of that other leading theatre practitioner and

playwright, Richard Brinsley Sheridan.

Mary had a brief but dazzlingly successful career at the

Drury Lane Theatre beginning in 1776, performing in such roles as Juliet and

Cordelia in adaptations of Shakespeare, as well in comedies of the era,

including Sheridan’s. She even played the role of the pregnant Fanny in George

Colman’s The Clandestine Marriage, while carrying her second daughter

(who died soon after birth). Celebrity culture as we understand it today was

probably born during this period and actors were as famous for their off-stage

exploits as they were on-stage. Mary came under this curious spotlight, as her

every item of clothing was described in detail in the press, thus setting a

fashion for whatever attire ‘Mrs Robinson’ was courting that week. Every lover,

real or supposed, was reported in scandalous detail. Mary was often described

as the most beautiful woman in the land and reported reactions confirm this

(though this is not always reflected in her portraits, even Romney’s and

Gainsborough’s); but she was also one of the most scandalous women. The

contemporary taste for satirical engravings testify to the circulating rumours,

as well as to the frequently depicted cuckold status of Tom Robinson, whose sexual

infidelities had increasingly distanced Mary. Pursued by a variety of dandies,

philanderers, rakes and libertines, it was her relationship with Prince George

(later Regent and King George IV) that was most prominently commented upon and

satirized. This affair was conducted by public flirtations at the theatre, and

by secret assignations at Kew and Windsor. Although George (who was some years

younger than Mary) was besotted, he was persuaded (by the King) to forego his

liaison with her, but he was also persuaded, if not actually blackmailed, by

Mary (with his revealingly sentimental correspondence) to, firstly, pay her a

large lump sum and, secondly, to provide a considerable annuity for her. On her

side, Mary wore a miniature of the young handsome George around her neck for

the rest of her life. (The annuity was paid, but irregularly.) The press

referred to the couple as Perdita and Florizel, after the principals of

Garrick’s re-working of The Winter’s Tale in which Mary had performed

before the Prince in 1779. She finally left the stage the following year, but

the ‘Perdita’ persona was to stick. (And long after her death, arguably to our

own day, given the titles of biographies.)

The Prince of Wales was at this time politically aligned

with the Whigs, and Mary, along with her aristocratic friend, Georgiana,

Duchess of Devonshire, campaigned for Charles James Fox in 1784. This marks the

beginning of Mary’s political affiliations, as well as the occasion for a short

affair with Fox himself. However, her great lover was neither the royal nor the

radical, but a military hero, Banastre Tarleton, just returned from the

American War of Independence, and who was as much the talk of the town (and the

press) as Mary herself. The couple possibly met at the studio of Sir Joshua Reynolds,

where both sat for portraits, which were soon after exhibited together

(knowingly). Tarleton, the scion of a Liverpool sugar and slave trading family,

and a war criminal by modern standards, proved relatively faithful to Mary

(until a final break in 1797). He still has a plaque marking his birth in Water

St., and there is a Tarleton Road and a place named Banastre too! As Liverpool

MP, he was a supporter of Fox (even his Tarleton ‘crop’ was the apparent

hairstyle of the Jacobins). An inveterate gambler, Tarleton’s debts were

frequently cleared by his Liverpool family, and he was implored to relinquish

his relationship with Mary in exchange for the largest of these bailouts. In

confusion, and to evade creditors, he fled to the continent in July 1783.

A distraught Mary followed him in a carriage, assuming

Dover to be his point of embarkation. Pregnant again, Mary suffered a

catastrophic collapse on the way to Kent, and a miscarriage. Exposure to the

elements contributed to an attack of a rheumatoid condition that resulted in

partial but permanent paralysis of her legs. Reunited with Tarleton, she

recuperated in France, the press reporting, not always accurately, on her

condition. One newspaper announced her death. She had previously visited France

under quite different circumstances, having seen (and possibly met) Marie

Antoinette, and immediately on her return, had introduced looser French fashion

into female London society, the Perdita Chemise, for one. Those days were over.

Mary

was largely away from Britain until early 1788. As she recovered, now in the

continuing care of her mother, Hester, and her daughter Maria Elizabeth, Mary

assisted Tarleton in the writing of his memoirs (as she had assisted him with

his political speeches). Since childhood, Mary had written poetry and prose,

and while in debtors’ prison she had published a volume of poems, Poems by

Mrs Robinson (1775) to be followed in 1777 by Captivity, a Poem;

she wrote several dramatic works, one of which she performed in. The Lucky Escape, a Comic Opera, Drury Lane, 1778, was never

officially published.

However,

her main literary career begins on her return from France. While she still

figured in the celebrity press (largely as a pathetic invalid), she was

increasingly commented upon in the literary press, her forthcoming

publications or works-in-progress either ‘puffed’ or reviled, depending on the

paper’s politics. Predictably, she immersed herself in the current literary

fashion. This was, in some ways unfortunate, because the Della Cruscan school

of poetry was then in the ascendent, noted for its lyricism of high sensibility

peppered with metaphors. The common disapprobative adjective of its style was

‘flowery’. (Some recent critics have re-cast it as a knowing community writing

ludic and burlesque entertainments.) The insistence upon ordinary speech in the

poetics of William Wordsworth, in the ‘Preface’ to The Lyrical Ballads,

a decade later was, in part, a reaction against this school. Writing in its

journal, The World, its chief poet, Robert Merry, conducted a public

(though page-based) flirtation with several women poets, and Mary joined in the

caper. This began her practice of writing under pseudonyms (for different

styles). At various times, not unlike an actress playing roles, she appeared as

Anne Frances Randall, Bridget, Horace Juvenal, Humanitas, Julia, Laura, Laura

Maria, Lesbia, Oberon, Portia, Sappho, as well as Tabitha Bramble (for lighter

works). Horace Juvenal, for example, as the over-egged pseudonym suggests,

produced the satire Modern Manners in 1793. Mary’s facility and speed, as well as eye for detail and ear for

metrical inventiveness, turned her into a competent staff writer, producing

copy for various journals, the Oracle and the Morning Post in

particular, poems at first, but later journalistic prose and comment pieces. A

good deal of this work was scattered and not collected, although she was quick

to publish volumes of poetry under her own name, first pamphlets such as Ainsi

va le Monde in 1790, which was a favourable reaction to the French

Revolution, and was well received. (It contrasts with her 1791 pamphlet Impartial

Reflections on the Present Situation of the Queen of France and her poem Monody

to the Memory of Marie Antoinette Queen of France of 1793, which reflect

her growing ambivalence to the violence of the Revolution.) She had great hopes

for her full-length collection, Poems by Mrs Robinson of 1791, which was

published by subscription in a lavish edition (and many of her former

associates were subscribers). The publisher went out of business and Mary

derived no income from the exertion, even from a popular digest edition. Mary

increasingly doubted the probity of publishers.

Mary

did not leave the theatre world entirely behind, both as audience and

dramatist, although a new generation of directors and actors, John Philip

Kemble and Sarah Siddons, for example, were keen to distance themselves from

the theatre scandal of earlier years, with which the name of ‘Perdita’ was

indelibly linked. Her satire Nobody, about women gamesters, was

mounted at Drury Lane in 1794, but was a reputational and box-office disaster.

The verse play The Sicilian Lover: A Tragedy in Five Acts was published

in 1796, after Mary suspected her plotlines were being plaigiarised, while the

theatre dithered over whether to stage it, before turning it down.

The

English Sappho, as Mary was sometimes called, published Sappho and Phaon in

1796, an account, borrowed from Pope’s versions of Ovid, of Sappho’s

heterosexual and suicidal obsession with the rakish Phaon. Cast into

‘legitimate’ sonnets, and based on Petrarch’s Canzoniere, it mixed

ancient Greek narrative with the form and content of the earliest sonnets. In

the event Mary produced the first English sonnet sequence since the

Renaissance, a literary milestone in itself. Whether or not Sappho and Phaon

are avatars for Mary and Tarleton (and whether or not that matters), Mary

produced a poetic tour de force of form and feeling. (It was through these

poems that I first encountered Robinson and produced ‘Tabitha and Thunderer’;

see links at the head of this post.)

Mary

turned her hand to writing novels in the last prolific decade of her life, and

produced seven (and left one unfinished). Her novels, as was then common,

contained her poems, and reviews often noted these as highlights of the

volumes. Her first, Vancenza; or the Dangers of Credulity (1792), was a

great success. Selling in vast quantities, it passed through a number of quick

new editions. Distantly autobiographical, it was a fashionable Gothic novel,

but with a political tinge. The Widow, or a Picture of Modern Times, an

epistolary novel, followed two years later, with its attacks on the

follies of the fashionable world, but it was not a commercial success (too many

copies had been printed). Angelina (1796) initially sold well, but

stalled. Its radicalism, concerning rank and the neglect of innate talent, with

its modern-sounding description of marriage as ‘legalised prostitution’, was

praised in a review by feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. Set during the upheavals

of the French Revolution, Hubert de Sevrac, a Romance, of the Eighteenth

Century (1796) carries a Godwinian ethic. In 1797, Walsingham; or, the

Pupil of Nature appeared, whose plot revolves around the Wollstonecraftian

theme of women’s property rights; this novel is probably the one most admired

today. [Currently on order: possible report to follow!] The False Friend, a

Domestic Story (1799) goes one stage further and makes the heroine an open

advocate of Wollstonecraft herself. The villain was read (by knowing reviewers)

as a portrait of Tarleton; although the parallels are not absolute, Tarleton

was indeed a false friend by the end of his long relationship with Mary. (He

suddenly married in 1798, and lived until 1833, now a Tory, stoutly defending

slavery on the eve of its abolition). The Natural Daughter (1799) which

explores the dilemma of being a single mother, is perhaps her most

autobiographical novel. This summary suggests a sequence of intellectual

novels, but they are driven by strong and clearly defined characters. Several

were translated into French and German. (Mary also translated works into

English from German.) Oddly, Mary did not find writing easy. She reports a

number of times on the sheer exhaustion of literary composition, and her output

in all her chosen genres is testimony to her resilience and tenacity, in the

face of her disabilities.

Mary had always been a social creature but found

herself, after the death of mother Hester in 1793, and after the final break

with Tarleton, alone with her loyal daughter. (Maria Elizabeth also published a

novel and possibly continued Mary’s unfinished Memoirs (1801)). Mary

attempted to replace the glittering fashionable London world with a smaller

circle of writers and thinkers, as her own thinking became more radical (and

complex) in reaction to a general acceptance of Rousseau’s philosophy, and

excitement (and horror) at events in Revolutionary France, but also in relation

to homegrown politics, far to the left of her Foxite Whigism. Growing

repression at home under Pitt’s government nurtured her radicalism. She

cultivated a circle of women writers, such as Elizabeth Inchbold, Mary Hays and

Jane Porter (and may have met Charlotte Smith, her nearest literary analogue).

She knew both the rationalistic radical and novelist William Godwin, with whom

she had a relationship, involving both intimacy and animosity, and with

Godwin’s wife, the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, whose views on women’s

property rights and female education made a profound impression on Mary (and

are reflected not only in her final novels but in her non-fiction, notably her

1799 polemic ‘A Letter to the Women of England, on the Injustice of

Subordination’). Older writer friends, like Merry and the satirist Peter Pindar

(John Wolcot), remained faithful, but she formed one crucial younger attachment

at the end of her life. When she replaced Robert Southey as ‘poetry editor’ of The

Morning Post – though she was more of a regular contributor and

correspondent – she came to work, exchange poems, and discuss poetry with

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who was staff writer on politics. She read The

Lyrical Ballads, whose first (anonymous) edition Coleridge and Wordsworth

had published in 1798, but which had yet to make an impression, let alone

revolutionise English poetry. Mary’s own favourite among her books, Lyrical

Tales (1800), is profoundly influenced by it (as her work was influential

upon the work of the two collaborators). She also wrote poems to Coleridge, one

of which alludes to his ‘Kubla Khan’ which was not published until many years

later.

In

the last months of her life, Mary moved to Maria Elizabeth’s cottage near

Windsor. But this proved to be far from a rural seclusion. She enjoyed frequent

visits from members of her literary circle, but was constantly writing and

editing, even while she was failing in health. She continued producing

commercial magazine verse for various journals; she proudly listed over 70

poems written in her last year. She remained, and died, in debt, and, indeed,

was almost imprisoned again. Her prose pieces published in the Morning Post,

this time under the title ‘The Sylphid’, which adopt the viewpoint of an

invisible observer, comment on contemporary manners, fashion, and the neglect

of talent. She arranged a three volume Poetical

Works, which was seen through the press in 1806 by her daughter. A single

volume edition appeared in 1824.

Mary

died the day after Christmas Day 1800 of heart failure. She was buried in

Windsor, with Godwin and Peter Pindar as sole mourners. The grave is still

there.

2022-2023

Select Bibliography (other books will be collected into this happy list)

Byrne, Paula. Perdita: The

Life of Mary Robinson. London: Harper Perennial, 2005. (That’s the first

biography I read.)

Feldman, Paula, R., and Daniel

Robinson. eds. A Century of Sonnets. Oxford,

New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Gristwood, Sarah. Perdita:

Royal Mistress, Writer, Romantic. London: Bantam Press, 2005. (This is the

second biography I’ve read, more recently.)

Robinson, Mary. The Poetical Works of the Late Mrs.

Mary Robinson, Volume 1. London:

Richard Phillips, 1806; Forgotten Books facsimile reprint; London, 2018.

Robinson,

Mary. The Poetical Works of the Late Mrs. Mary Robinson, Volume 2. London:

Richard Phillips, 1806; Scholar Select facsimile reprint; np: nd.

Robinson,

Mary. The Poetical Works of the Late Mrs. Mary Robinson, Volume 3. London:

Richard Phillips, 1806; facsimile reprint; Miami: nd (possibly 2008)

Robinson, Mary. Poetical Works of the Late Mrs. Mary Robinson: Including The Pieces Last Published, The Three Volumes Complete in One. London: Jones and Company, 1824; Forgotten Books facsimile reprint: London, 2015. (My copy of this is shit, with many blank pages and odd ones with only a few words on it, or only the punctuation, like a conceptual piece, but it is useful to see how the three volumes were sardine-canned into this one volume. By 1824, it is not clear who was still reading Robinson. The Romantics were taking central stage and women writers (say, Mary Tighe who influenced Keats, as well as Mary) were relegated to second-rate-hood. It awaited the pioneering (mostly women) critics of the 1980s onwards to recover these figures (I tried to accommodate as many women sonneteers as I could in the ‘14 Standards’ part of British Standards: see here: Pages: Robert Sheppard: 14 Standards from British Strandards is complete as one sonnet appears at the virtual WOW Festival 2020 (hub post)). But Mary had to still put up with the ‘Perdita’ notoriety. You see Coleridge and Jane Porter edging away from contagion with the iniquity of Regency days, and Porter denying even having known her. Without being too pompous, it is worth remembering that even Jesus suffered denial from a disciple.)

*

Locating Robert Sheppard: email: robertsheppard39@gmail.com website: www.robertsheppard.weebly.com Follow on Twitter: Robert Sheppard (@microbius) / Twitter latest

blogpost: www.robertsheppard.blogspot.com